Richard III (1955 film)

| Richard III | |

|---|---|

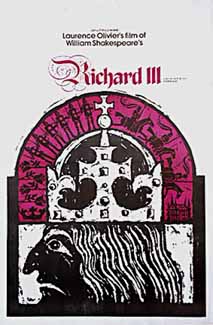

re-release theatrical poster |

|

| Directed by | Sir Laurence Olivier |

| Produced by | Sir Laurence Olivier Sir Alexander Korda (uncredited) |

| Written by | Play: William Shakespeare Interpolations: Colley Cibber David Garrick |

| Starring | Sir Cedric Hardwicke Sir John Gielgud Sir Laurence Olivier Paul Huson Andy Shine Ralph Richardson |

| Music by | William Walton |

| Cinematography | Otto Heller |

| Editing by | Helga Cranston |

| Distributed by | London Films |

| Release date(s) | 16 April 1955 (UK) 11 March 1956 (US) |

| Running time | 161 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £6,000,000 (estimated) |

| Gross revenue | US$2,600,000 (USA) £400,000 (GB) |

| Preceded by | Hamlet |

Richard III is a 1955 British film adaptation of William Shakespeare's historical play Richard III, including elements of Henry VI, Part 3. It was directed and produced by Sir Laurence Olivier, who also played the lead role. The cast includes many noted Shakespearean actors, including a quartet of acting knights. The film depicts Richard plotting and conspiring to grasp the throne from his brother King Edward IV, played by Sir Cedric Hardwicke. In the process, many are killed and betrayed, with Richard's evil leading to his own downfall. The prologue of the film states that history without its legends would be "a dry matter indeed", implicitly admitting to taking artistic licence with the events of the time.

Of the three Shakespearean films directed by Olivier, Richard III received the least critical praise at the time, although it was still acclaimed, and it was the only one not to be nominated for Best Picture at the Academy Awards, though Olivier's acting performance was nominated. The film gained popularity through a re-release in 1966, which broke box office records in many cities.[1] Many critics now consider Olivier's Richard III his best screen adaptation of Shakespeare. The British Film Institute has pointed out that given the enormous TV audiences it received in 1955, the film "may have done more to popularize Shakespeare than any other single work".[2]

Contents |

Production

Background

Of Olivier's three Shakespeare films, Richard III had the longest gestation period: Olivier had created and been developing his vision of the character Richard since his portrayal for the Old Vic Theatre in 1944. After he had made Shakespeare films popular with Henry V and Hamlet, the choice of Richard III for his next adaptation was simple, as his Richard had been widely praised on stage. For the stage production, Olivier had modelled some of the crookback king's look on a well-known theatrical producer at the time, Jed Harris, whom Olivier called "the most loathsome man I'd ever met".[3] Years later Olivier discovered that Walt Disney had also used Harris as his basis for the Big Bad Wolf in the film The Three Little Pigs.[4] Alexander Korda, who had given Olivier his initial roles on film, provided financial support for the film.[4]

Screenplay

Most of the dialogue is taken straight from the play, but Olivier also drew on the eighteenth century adaptations by Colley Cibber and David Garrick, including Cibber's line, "Off with his head. So much for Buckingham!". Like Cibber and Garrick, Olivier's film opens with material from the last scenes of Henry VI, Part III, in order to introduce more clearly the situation at the beginning of the story. Other key changes include the seduction of Anne being split into two scenes instead of one, the character of Queen Margaret being cut entirely, and the execution of Clarence being abridged.[5] These cuts were made to maintain the pace of the film and to cut down the running time, as a full performance of the play can run upwards of four hours.

Filming

Gerry O'Hara was Olivier's assistant director, on hand to help since Olivier was acting in many, if not most, of the scenes.[4]

Olivier made the unusual decision to directly address the film audience by looking into the camera while delivering his soliloquies, something not often done before in film. He made this choice in order to make the audience feel as though they were a part of Richard's schemes.

Most of the film was shot in at Shepperton Studios, but the Battle of Bosworth Field abruptly opens up the setting, as it was shot outdoors, in the Spanish countryside. During one sequence, Olivier suffered an arrow wound to the shin. Fortunately, it was on the leg Richard was supposed to limp on, allowing the scene to continue. Though for most of the film he kept the story in the confines of a filmed play,[1]

During filming, Olivier's portrait was painted by Salvador Dalí. The painting remained one of Olivier's favourites until he had to sell it to pay for his children's school fees.[4]

Cinematography

The cinematography for the film was by Otto Heller, who had worked on many European films before coming to the UK in the early 1940s. The film uses the Technicolor process, which Olivier had earlier rejected for his Hamlet after a row with the company.[4] The use of Technicolor resulted in bright, vibrant colours - some have even commented that the film looks like an oil painting.[6] Korda had suggested that Olivier also use the new extreme widescreen format, CinemaScope, but Olivier thought it was nothing more than a gimmick designed to distract the audience from the true quality of the film, and chose the less extreme VistaVision format instead.[4]

Music

The score was composed by Sir William Walton, who worked on all of Olivier's films except The Prince and the Showgirl. He composed a rousing score filled with pomp and circumstance, to add to the feel of pageantry. The music was conducted by Muir Mathieson, who collaborated on all of Olivier's films. The film's music was also used for a reading of the play on audio cassette featuring John Gielgud.[7] Walton used the main theme throughout the film, especially towards the closing scenes.

Plot

...The history of the world, like letters without poetry, flowers without perfume, or thought without imagination, would be a dry matter indeed without its legends, and many of these, though scorned by proof a hundred times, seem worth preserving for their own familiar sakes. The following begins in the latter half of the 15th century in England, at the end of a long period of strife set about by rival factions for the English crown, known as the Wars of the Roses. The Red Rose being the emblem for The House of Lancaster. The White for The House of York. This White Rose of York was in its final flowering at the beginning of the Story as it inspired William Shakespeare...

– Preamble

King Edward IV of England (Sir Cedric Hardwicke) has been placed on the throne with the help of his brother, Richard (Sir Laurence Olivier). After Edward's coronation in the Great Hall, Richard contemplates the throne, before advancing towards the audience and then addressing them, delivering a speech that outlines his physical deformities, including a hunched back and a withered arm. He goes on to describe his jealousy over his brother's rise to power in contrast to his lowly position.

He dedicates himself to task and plans to frame his brother, George, Duke of Clarence (Sir John Gielgud), for conspiring to kill the King, and to have Clarence sent to the Tower of London. Having confused and deceived the King, Richard proceeds with his plans and Clarence is murdered, drowned in a butt of wine by enlisting two ruffians (Michael Gough and Michael Ripper) to carry out his dirty work. Richard goes on to woo and seduce the Lady Anne (Claire Bloom), and though she hates him for killing her husband and father, she cannot resist and ends up marrying him.

Richard then orchestrates disorder in the court, fuelling rivalries, and setting the court against the Queen consort, Elizabeth (Mary Kerridge). The King, weakened by exhaustion, appoints his brother, Richard, as Lord Protector, and dies. Edward's son, soon to become Edward V (Paul Huson), is met by Richard whilst en route to London. Richard has the Lord Chamberlain, Lord Hastings (Alec Clunes) arrested and executed, and forces the young King, along with his younger brother the Duke of York (Andy Shine), to have a protracted stay at the Tower of London.

With all obstacles now removed, Richard enlists the help of his "cousin Buckingham (Ralph Richardson)" to alter his public image, and to become popular with the people. In doing so, Richard becomes the people's first choice to become the new King.

Buckingham had aided Richard on terms of being given yet another title and the income from the accompanying land grant, but balks at the idea of murdering the two princes. Richard then asks a minor knight, Sir James Tyrrel (Patrick Troughton), eager for advancement, to have young Edward and the Duke of York killed in the Tower of London. On requesting his earldom at Richard's coronation, Buckingham is met with Richard's response: "I'm not in the giving vein today!" Buckingham then fears for his life and joins the opposition against Richard's rule.

Richard, now fearful due to his dwindling popularity, raises his army to defend his throne and the House of York against the House of Lancaster, led by Henry of Richmond (Stanley Baker), at Bosworth Field. Before the battle, however, Buckingham is captured and executed.

Before the battle, Richard is haunted by the ghosts of all those he has killed in his bloody ascent to the throne, and he wakes screaming. Richard composes himself, striding out to plan the battle for his generals, and gives his motivational speech to his forces:

"Conscience is but a word that cowards use,

Devised at first to keep the strong in awe!

Conscience avaunt!

(Aside) "Richard's himself again."

"March on! Join bravely! Let us to it pell mell.

If not to heaven, then hand in hand to hell!"

The two forces engage in battle, with the Lancastarians having the upper hand. Lord Stanley (Laurence Naismith), whose loyalties had been questionable for some time, betrays Richard, and allies himself with Henry. Richard sees this and rushes out to fight Henry. However, Richard is knocked off his horse, loses his cherished crown, and is soon lost in the battle, searching desperately for Henry. He then cries out: "A horse! A horse! My kingdom for a horse!"

Richard then spots Lord Stanley, and engages him in single combat. Before a victor can emerge, the Lancastarian troops charge Richard, and fatally wound him. Richard convulses in several spasms and offers his sword to the sky before dying. Stanley orders Richard's body to be taken away, and then finds Richard's crown in a thorn bush. He then proceeds to offer it to Henry, leaving the crown of England in safe hands once again.

Cast

Olivier elected to cast only British actors. Since the film was financed by Alexander Korda and produced by his London Films, obtaining the required actors was not difficult, as many actors were contractually obliged to London Films. As with most films with ensemble casts, all the players were billed on the same tier. However, Olivier played the title character and occupies the majority of screen time and therefore could be considered the lead actor.

When casting the supporting roles, Olivier chose to fortify the already impressive cast with seasoned veterans, such as Laurence Naismith, and with promising newcomers, such as Claire Bloom and Stanley Baker. For the murderers, Olivier originally wanted John Mills and Richard Attenborough. However, Mills thought the idea might be regarded as "stunt casting", and Attenborough had to pull out due to a schedule clash.[4] The film's marketers in the US picked up on the fact that the cast included four knights (Olivier, Richardson, Gielgud and Hardwicke) and used this as a selling point.[4]

The House of York

- Sir Cedric Hardwicke as King Edward IV of England, the newly-crowned King of England, who, with the aid of his brother, Richard, has secured his position by wresting it from Henry VI of the House of Lancaster. Hardwicke was a stage actor who had moved to the U.S. to pursue a film career. He was mainly known for supporting roles in Hollywood. This marked his only appearance in a film version of a Shakespeare play.

- Sir John Gielgud as George, Duke of Clarence, brother of the new King. Gielgud's standing as the great stage Shakespearean of the decades immediately preceding Olivier's career was a cause of a certain enmity on the part of Olivier, and it was known that he disapproved of Gielgud's "singing" the verse (i.e. reciting it in an affected style that resembles singing).[8] Gielgud's casting in this film can be seen as a combination of Olivier's quest for an all-star cast, and the fact that Olivier had rejected Gielgud's request to play the Chorus in Olivier's 1944 adaptation of Henry V.[4]

- Sir Laurence Olivier as Richard, Duke of Gloucester, later King Richard III), the malformed brother of the King, who is jealous of his brother's new power, and plans to take it for himself. Olivier had created his interpretation of the Crookback King in 1944, and this film transferred that portrayal to the screen.[4] This portrayal earned Olivier his fifth Oscar nomination, and is generally considered to be one of his greatest performances; some consider it his best performance in a Shakespeare play.

- Paul Huson as the Prince of Wales (later, for a brief while, King Edward V), the eldest son of the King, who holds many strong beliefs, and wishes one day to become a Warrior King. This was Huson's only performance on screen, as he went on to become an artist and an author.

- Andy Shine as the Duke of York, the younger son of the King. This was Shine's second and last on-screen performance, after his role in That Lady.

- Helen Haye as the Duchess of York, the mother of the King. Haye worked regularly for Alexander Korda.

- Pamela Brown as Jane Shore, the King's mistress. Brown primarily worked in British films, until she branched out into Hollywood in the 1960s with roles in such films as Cleopatra.

- Sir Ralph Richardson as the Duke of Buckingham, a corrupt official, who sees potential in Richard's plans and eventually becomes a fellow conspirator when Richard goes too far. Richardson was a lifelong friend of Olivier's, and was one of the great four theatrical knights of the 20th century along with Alec Guinness, Gielgud and Olivier. At first, Olivier wanted Orson Welles as Buckingham, but felt an obligation towards his longtime friend. (Olivier later regretted this choice, as he felt that Welles would have added an element of conspiracy to the film.)[4]

- Alec Clunes as The Lord Hastings (Lord Chamberlain), a companion and friend of Richard who is accused of conspiracy by Richard and is abruptly executed. Clunes was primarily a stage manager, giving people such as Peter Ustinov their big break.

- Laurence Naismith as The Lord Stanley. Stanley has a certain dislike for Richard and is not totally willing in his cooperation with him. Stanley eventually betrays Richard at Bosworth and engages him in a one-on-one duel. Naismith was a veteran actor, known mostly in the film industry for bit parts and supporting roles.

The House of Lancaster

- Mary Kerridge as Queen Elizabeth, Queen Consort of Edward. Kerridge did not make many screen appearances, though she did sometimes work for Alexander Korda.

- Clive Morton as The Lord Rivers, brother of the Queen Consort. Morton was a British actor who mainly played supporting roles on screen.

- Dan Cunningham as The Lord Grey, brother of the Queen Consort. Cunningham's role in Richard III was one of his few screen appearances.

- Douglas Wilmer as The Lord Dorset, eldest son of the Queen Consort and stepson of the King. Wilmer had several supporting roles in Hollywood blockbusters and was a noted Sherlock Holmes on British television.

- Claire Bloom as The Lady Anne, a widow and an orphan thanks to the acts of Richard, though she cannot resist his charms and eventually becomes his wife. Bloom became a celebrated Shakespearean actress, and made several screen appearances.

- Stanley Baker as Henry, Earl of Richmond (later Henry VII, first of the House of Tudor). Henry, Richard's enemy, and Lord Stanley's stepson claims his right to the throne, and meets Richard at Bosworth. This was one of Baker's first roles as a hero, which was followed by a strong film career, including a role in The Guns of Navarone and the leading role in Zulu.

Reception

Richard III was released in the UK on 16 April 1955, with Queen Elizabeth II attending the premiere.[4] Alexander Korda had sold the rights to the film to NBC in the U.S. for $500,000 and the film was released in the U.S. on 11 March 1956 both on television and in cinemas.[4] It was not shown during prime time on television, but rather in the afternoon. The film was generally well received by critics, with Olivier's performance earning particular notice, but due to its simultaneous release through television and cinemas in the U.S., it was a box office failure. However, the airing on U.S. television received excellent ratings, estimated at between 25 and 40 million.[9] In addition, when the film was reissued in 1966, it broke box office records in many US cities.[1]

The review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes records that 100 percent of its collected reviews of the film are positive.[10] However, the reviewer for the AllMovie website criticizes Olivier's direction for being far more restricted in its style in comparison to the bold filming of Henry V, or the moody photography of Hamlet, and Olivier the actor for dominating the production too much,[11] (although the character of Richard certainly dominates Shakespeare's original play). There were some complaints about geographical inaccuracies in the film. In response, Olivier wrote in The New York Times: "Americans who know London may be surprised to find Westminster Abbey and the Tower of London to be practically adjacent. I hope they'll agree with me that if they weren't like that, they should have been."[12]

The film's failure at the U.S. box office, however, along with Korda's death, ended Olivier's career as a Shakespeare film director. Olivier had been planning to make Macbeth, but one of his other major backers, producer Mike Todd, died in a plane crash.[4]

Awards

In contrast to Olivier's previous work, Richard III was only nominated for a single Academy Award: Academy Award for Best Actor. It was Olivier's fifth nomination in the category, though the award was won by Yul Brynner for his performance in The King and I. Richard III was the second film to have won both Best Film awards at the BAFTAS. It dominated that year's awards ceremony, winning, in addition to the two Best Film awards, the award for Best British Actor. It was also the first winner of the newly created Golden Globe Award for Best English - Language Foreign Film, which had been split from the Best Foreign Film Award. Other awards won by the film include the Silver Bear Award at the 6th Berlin International Film Festival[13] and the David di Donatello Award for Best Foreign Production. The Jussi Award was given to Olivier for Best Foreign Actor.[14]

Influence

Olivier's Richard III may have done more to popularize Shakespeare than any other piece of work.[9] According to the British Film Institute, the 25–40 million viewers during its airing on US television, "would have outnumbered the sum of the play's theatrical audiences over the 358 years since its first performance."[9]

Johnny Rotten from the Sex Pistols stated in his autobiography, Rotten: No Blacks, No Irish, No Dogs, that Olivier's performance as Richard had a large influence on him. Scenes from the film were used in the Sex Pistols' documentary The Filth And The Fury.[15]

The film was the inspiration and source of parody for the BBC Television series, Blackadder.[16] For instance, Peter Cook's performance in the first episode of The Black Adder was a parody of Olivier's Richard III. The crown motif shown throughout the film is also quoted. "Additional Dialogue by William Shakespere" was a credit to the bard that lasted until Season 3.

DVD release

The film has been released outside the U.S. on DVD several times, but these releases are copies of the unrestored and cropped film. In 2004, Criterion digitally restored the film in its original widescreen format and re-constructed it to match the release script. It was released in a 2-disc special edition, including an essay by film and music historian Bruce Eder, an interview with Olivier, and other numerous special features.[17] The DVD is subtitled in English, with a Dolby Digital 2.0 Mono audio track. The DVD also contains a commentary by Russell Lees and John Wilders. The second disc of the DVD features a 1966 BBC interview with Olivier by Kenneth Tynan entitled Great Acting: Laurence Olivier. It also contains a gallery of posters, production stills and two trailers.

Notes and references

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Bruce Eder. "Richard III". Criterion. http://www.criterion.com/asp/release.asp?id=213&eid=344§ion=essay&page=1. Retrieved 2006-07-08.

- ↑ Michael Brooke. "Richard III (1955)". British Film Institute. http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/467017/index.html. Retrieved 2006-07-12.

- ↑ Margaret Gurowitz. ""Me, drunk? Ha! You should see Buckingham!"". Richard III Society, American Branch. http://www.r3.org/onstage/drunk.html. Retrieved 8 July 2006.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 Coleman, Terry (2005). Olivier. Henry Hilt and Co. ISBN 0-8050-7536-4., Chapter 20

- ↑ Ed Nguyen. "Richard III DVD Review". DVD Movie Central Review. http://www.dvdmoviecentral.com/ReviewsText/richard_iii.htm. Retrieved 2 April 2006.

- ↑ DVD Beaver review of Richard III - Criterion Collection Edition, DVD Beaver, Review written by Gary W. Tooze, retrieved on 7-13 2006

- ↑ "Walton: Richard III, Macbeth". amazon.com. http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B000000AKM/104-7370788-9975120?v=glance&n=5174. Retrieved 2006-07-08.

- ↑ http://romeojuliet_uno.tripod.com/history1935.html#c

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 "Richard III Review". Screenonline (British Film Institute). http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/467017/index.html. Retrieved 2006-07-08.

- ↑ "Richard III Review". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/1017538-richard_iii/. Retrieved 2006-07-08.

- ↑ Jeffrey M. Anderson. "Richard III Review". UGO. http://www.allmovieportal.com/m/1955_Richard_III77.html.

- ↑ Robertson, Patrick (2001). Film Facts. Billboard Books. ISBN 0-8230-7943-0.

- ↑ "6th Berlin International Film Festival: Prize Winners". berlinale.de. http://www.berlinale.de/en/archiv/jahresarchive/1956/03_preistraeger_1956/03_Preistraeger_1956.html. Retrieved 2009-12-27.

- ↑ "Awards for Richard III (1955)". imdb.com. IMDB. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0049674/awards. Retrieved 9 July 2006.

- ↑ Lydon, J (1995). Rotten: No Blacks, No Irish, No Dogs. Picador. ISBN 0-312-11883-X.

- ↑ "Amazon Editorial Review". amazon.com. http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/6302969271/104-4105447-8067916?v=glance&n=404272. Retrieved 8 July 2006.

- ↑ "Richard III DVD". Criterion. http://criterion.com/asp/release.asp?id=213. Retrieved 2006-07-08.

See also

- Shakespeare on screen: Other performances and adaptations of Richard III

External links

- Richard III at the Internet Movie Database

- Richard III at Allmovie

- Richard III (1955 film) at the TCM Movie Database

- Richard III at Rotten Tomatoes

- Criterion Collection essay by Bruce Eder

- DVD Movie Central Review

- MSN Movies Page

- Screenonline Page

| Awards and achievements | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by The Wages of Fear |

BAFTA Award for Best Film from any Source 1956 |

Succeeded by Gervaise |

| Preceded by Hobson's Choice |

BAFTA Award for Best British Film 1956 |

Succeeded by Reach for the Sky |

| Preceded by split from Best Foreign Language Film |

Golden Globe Award for Best English-Language Foreign Film 1957 |

Succeeded by Woman in a Dressing Gown |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||